The healthcare landscape is profoundly transformed, driven by technological innovation, shifting patient demographics, evolving care delivery models, and an intensified focus on health equity. Within this dynamic environment, the nursing profession, comprising the largest segment of the healthcare workforce at nearly 4.7 million registered nurses (RNs) nationwide, plays an increasingly critical and indispensable role.

Nurses operate at the intersection of health, education, and communities, uniquely positioned to address complex health challenges and improve outcomes. However, the profession faces significant pressures, including workforce shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising patient acuity, and the need to address longstanding health inequities.

Recognizing these challenges and opportunities, landmark reports such as the National Academy of medicine’s (NAM) The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity emphasize the potential for nursing education to evolve and meet these challenges. Preparing nurses for the future requires robust education, supportive work environments, and the autonomy to practice to the full extent of their training. Nursing education must equip graduates with new competencies to leverage technology, manage population health, work effectively in interprofessional teams, address social determinants of health (SDOH), and lead change within complex systems. This report synthesizes recent evidence to provide a forward-looking overview of the key trends and advancements shaping nursing education, focusing on expectations for 2025. It examines technology integration, curriculum content and pedagogy shifts, strategies for addressing workforce challenges, the growing emphasis on equity and social context, and the rise of specialization pathways.

1. Industry 4.0 and the Nursing Sector

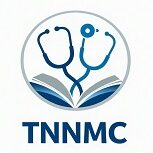

Technology-enabled change is evolving rapidly within nursing practice, and nursing education must change accordingly. More programs are integrating advanced tools that enrich learning, prepare students for practice and to work in a digitally actionable health care setting. By 2025, the top technologies present in nursing curricula include high-fidelity simulation, virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), artificial intelligence (AI) and telehealth platforms.

1.1 Highfidelity simulation (HFS)

High-fidelity simulation using computerized manikins in realistic clinical settings, continues to be a mainstay of nursing education. It is a safe, controlled space in which learners can practice technical skills, develop clinical judgment and learn from errors without the risk of causing harm to patients. It’s harnessed in areas such as to teach complex skills including medication administration and emergency response or to deal with complicated patient scenarios.

Research shows over and over again the positive effects of HFS on learning outcomes. HFS is however shown to significantly improve nursing students` knowledge, skills, confidence, satisfaction and critical thinking skills through systematic reviews and meta-analyses. For instance, studies show HFS has positive effects on performance in resuscitation situations and improves confidence in drug administration.

You must structure your time to prepare (prebriefing/briefing), step into the moment that is participation, and debrief out to ensure the rest of the learning process post-presentation/event. Challenges include cost of equipment, faculty training, and considerable time spent in scenario and debrief development. Its demonstrated efficacy, however, ensures that HFS is a critical component to help close the theory-practice gap.

1.2 Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR)

Emerging technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are being integrated into nursing education to introduce new clinical learning experiences and patient interactions. VR fully immerses me in a digital world, whereas AR overlays information on the world around me.

These technologies enable students to encounter real-world scenarios, practice procedures and gain decision-making abilities safely and repeatedly. Methodological literature reviews and meta-analyses systematically analyzed the usefulness of immersive VR/AR in nursing training and found significant improvement in students’ knowledge, technical skills and retention of skills, cognitive performance, and satisfaction.

Students say they prefer VR for its experiential quality. VR/AR may recreate experiences that would be difficult to replicate otherwise (e.g., accessing certain patient populations, rare emergencies, or even investigating SDOH within virtualized communities). Although there are barriers such as cost, technical specifications and even possible side effects (like simulation sickness ), VR/AR consider to be a big trend in Learning with the ability to create a more realistic and immersive experience.

1.3 → Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is positioned to play a major role in health care delivery, as well as nursing education. For education, AI can be found in personalized learning platforms, intelligent tutoring systems, AI-based student support chatbots, and programs for automating administrative tasks such as grading and scheduling.

By analyzing their patterns of learning, AI can personalize the content used by students, give them instant feedback, and recognize which areas they struggle with, leading to a more tailored and effective learning experience. Teaching students how to use AI-driven clinical decision support tools, which facilitate students’ clinical judgment on complex data analysis for possible risk (such as sepsis protocols, fall risk) and evidence-based intervention, are also being incorporated into curricula. In addition, AI can produce highly realistic case studies and power advanced simulations, such as AI-augmented robots or virtual patients who can mimic human interaction more realistically.

Yet the use of AI raises profound ethical issues related to data privacy, algorithmic bias, transparency, and accountability. Nursing schools should address these issues by equipping students not only with technical skills to utilise AI tools, but also with critical thinking and ethical reasoning abilities, which will enable them to evaluate AI outputs and ensure their applications are fair. [4] Our focus will be to prepare nurses to work with AI, harnessing it as a tool to facilitate their training and enhance patient care rather than to replace the essential human care that only nurses can provide.

1.4 Telehealth Training Platforms

As a faster adoption of telehealth driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth competency has become an essential nursing skill. With more and more nursing programs incorporating telehealth training through a variety of approaches, including didactic content, simulations and dedicated clinical experiences (10), it is time to step back and evaluate the current landscape of telehealth training for nursing students.

Studies have integrated training in telehealth etiquette, virtual assessment skills, remote patient monitoring (RPM), legal and regulatory issues, reimbursement policies, platform technologies, and [1] ethical issues in virtual care into curricula. The use of simulation is significant, and involves standardized patients (either in-person or via video conferencing) and virtual case scenarios (e.g., utilizing tools such as VoiceThread) that allow students a unique opportunity to practice telehealth competencies.

Dedicated telehealth clinical practicums that immerse students in telehealth delivery with supervision are also on the rise. One example of those frameworks is the Four P’s which stands for Planning, Preparing, Providing and Performance Evaluation. A multimodal approach to prepare nurses for telehealth ensures mastery of digital communication, virtual assessment, the technology of telehealth (to include peripherals such as digital stethoscopes or cameras), and the specific details of providing care at a distance.

Table 1: Technological Advancements in Nursing Education

| Technology | Description | Educational Applications | Key Benefits | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Simulation (HFS) | Computerized manikins, realistic environments | Skill practice (med admin, emergencies), clinical judgment development, teamwork training, debriefing | Safe practice environment, improved knowledge, skills, confidence, critical thinking | |

| Virtual/Augmented Reality (VR/AR) | Immersive digital environments (VR), digital overlays on real world (AR) | Realistic scenario immersion, procedural practice, virtual patient interaction, exploring diverse settings (e.g., community health) | Enhanced knowledge, skills, retention, engagement; access to diverse experiences | |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Machine learning algorithms, predictive analytics, NLP, chatbots | Personalized learning paths, intelligent tutoring, automated grading/feedback, clinical decision support training, AI-enhanced simulations, case study generation | Individualized learning, efficiency, improved clinical judgment training, administrative task automation | |

| Telehealth Platforms | Videoconferencing, remote patient monitoring (RPM), store-and-forward tech | Didactic content delivery, simulated patient encounters (standardized patients), virtual clinical practicums, training on specific platforms and peripherals, tele-etiquette practice | Preparation for remote care delivery, increased access understanding, development of digital communication skills |

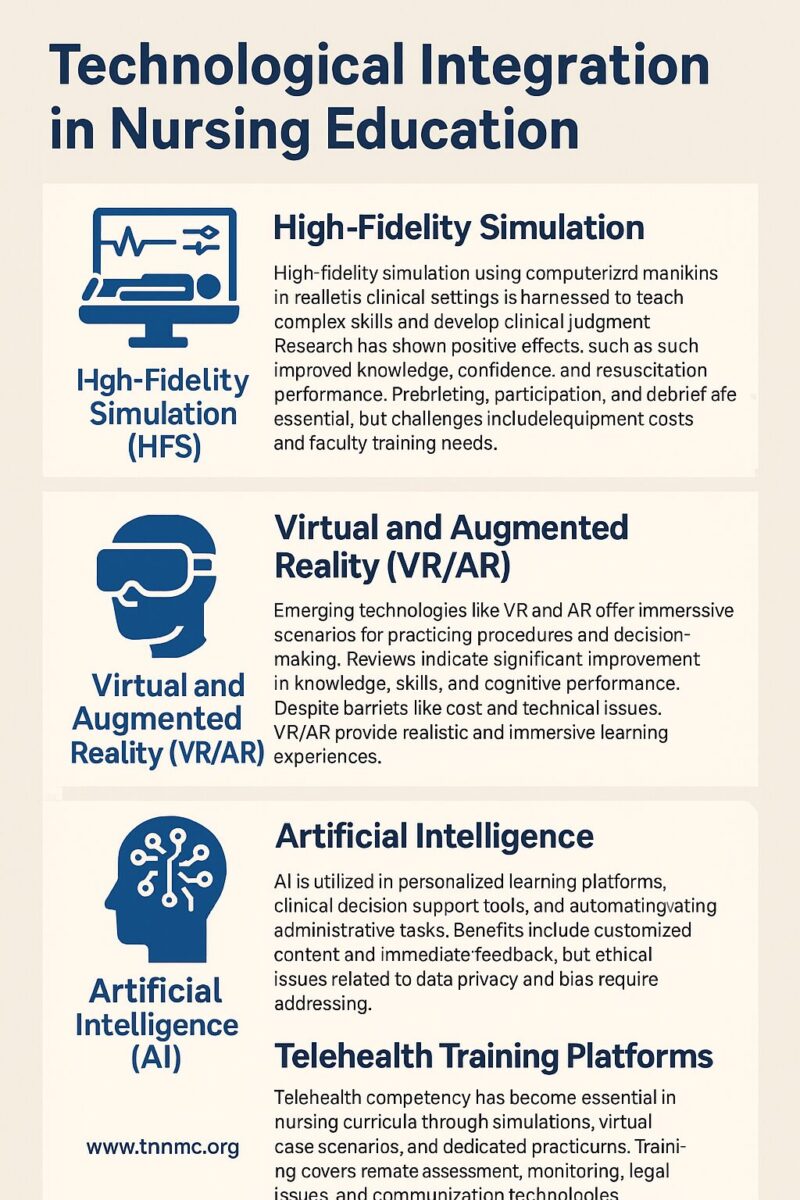

2. Trends in Curriculum Content: Curriculum Evolution

As technology becomes integrated, a significant transformation of the content of nursing curricula is underway to help prepare graduates to meet the complexities of health care and societal needs. Significant changes include an increased focus on population health, nursing informatics, genomics, interprofessional education, and mental health/well-being. These transformations arise in response to the need to eliminate health disparities, utilize data and technology to their fullest potential, recognize the genetic underpinnings of health, encourage interprofessional collaboration, and build resilience within the nursing workforce.

2.1 Population Health Management

There is an increasing acknowledgement that health outcomes are determined to a great extent by other factors beyond individual clinical care, including social determinants of health (SDOH). Nursing curricula are increasingly incorporating population health management principles. And this means preparing nurses to understand how to identify the health needs of particular populations (geographically, demographically or by condition), be aware of the influence of SDOH (such as housing and education, racial and ethnic discrimination and food access), and have the skills and tools to work collaboratively with communities and other sectors to promote health equity.

Curriculum integration strategies include dedicated courses, multiple courses with population health concepts as threads, and practical experiences such as public health departments, school systems, homeless shelters, and community clinics.

Learning activities could include analyzing population health data, creating community-based prevention and health promotion plans, engaging in service-learning projects responding to community needs (eg, health screenings, nutrition education), and applied simulation approach to outside world population-level challenges Key content areas include epidemiology, biostatistics, health policy and management, environmental health, care coordination for vulnerable populations, and program development and evaluation.

As a core domain, the AACN Essentials clarify that population health is an element of practice that includes managing population health, building partnerships, addressing socioeconomic context, and promoting equitable policies. This perspective enables nurses to become more than patient care providers, but instead begin to tackle the larger determinants of health in populations and promote health equity.

2.2 Nursing Informatics

Because technology is ubiquitous in healthcare, particularly in the form of electronic health records (EHRs), data analytics, and digital communication tools, the nursing profession is required to demonstrate strong informatics competencies. Nursing informatics is a subspeciality that uses technology to administer and share data, information, knowledge, and wisdom in nursing while integrating nursing science and computer and information science. Curricula are integrating informatics content to prepare graduates to use technologies for safe, efficient, and evidence-based care.

Informatics is one of the six competencies identified by the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative for pre-licensure nursing education. KSAs include how to use information and technology to communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision-making.

In a similar way, the AACN Essentials assigns Domain 8 to Informatics and Healthcare Technologies, serving to highlight the value of informatics processes and technologies to provide care, collect data, facilitate decision-making, and enhance knowledge.

Educational strategies include, integrated informatics content across courses, use of simulation to practice EHR documentation and clinical decision support tools, and incorporation of learning modules focusing on informatic principles.

Nurses must be trained in EHR utilization, data analysis as it pertains to quality improvement and telehealth usage and evaluation, and security regarding health information technologies. Focusing on technology in this way helps to ensure that nurses are trained to implement technology successfully in practice.

2.3 Genomics

Novel genomic technologies are defining health, risk of disease, and response to treatment, creating a need for genomic literacy in contemporary nursing practice. Nurses contribute to collecting family health histories, identifying patients who may be eligible for genetic testing, communicating genetic concepts and test results, providing support, and administering genetically informed therapies. But many nursing programs offer only minimal genomic education, in part because faculty were trained long before genomics became a routine part of care.

To address this discrepancy, approaches are being developed to incorporate genomics-based education into both undergraduate and graduate nursing curricula.

These strategies may take the form of stand-alone genomic courses, incorporating genomic concepts throughout other classes (e.g., health assessment, pharmacology, pathophysiology), or employing innovative educational practices, such as Team-Based Learning (TBL)3. As an active and student-centered approach to learning, TBL can increase the application and retention of knowledge.

The teaching materials focus on important skills such as understanding inheritance patterns, creating family trees, knowing when to suggest genetic testing, pharmacogenomics, and grasping ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI). To fill this gap, it’s essential to develop the teachers who will instruct on genomics and participate in ongoing projects.

This can be done by forming networks of supportive faculty, offering continuing education programs, and providing access to experts and resources (like genetic counsellors and toolkits) to help teachers feel more confident and capable in teaching genomics.

Critical to addressing this gap is the development of the faculty charged with teaching genomics and engaging in relevant and ongoing initiatives, which occur via the creation of faculty champion networks, continuing education programs, and access to expert personnel/resources (e.g., genetic counselors, toolkits) to increase the capacity and comfort level of faculty to teach genomics. Ideally, this will create nurses with the competence to apply genomic information to enhance patient care, thus supporting precision health and improving the safety of practice.

2.4. Interprofessional Education (IPE)

Task-sharing between professionals with independent disciplines is therefore a growing necessity for delivery of effective healthcare. Interprofessional education (IPE) is designed to prepare students and practitioners from two or more professions to learn about, from, and with each other to facilitate effective collaboration and improve health outcomes. Importance of IPE — IPE is described as essential for cultivating skills necessary for team-based care such as communication, teamwork, understanding roles and responsibilities, and shared decision-making. Teamwork and interprofessional partnerships are core competencies identified by QSEN and the AACN Essentials.

There are various ways to deliver IPE, such as through didactic sessions, workshops, simulation experiences, or shared clinical placements. Examples include:

Didactic Modules/Courses: Introduction to teamwork, and communication (for example, utilizing TeamSTEPPS® frameworks ), roles of different professions, and also patient-centered care through common coursework or seminars.

‘Simulation’: By creating simulated scenarios (e.g., care conferences, emergency response) in which students from multiple professions need to collaborate to provide patient care.

Community / Service-Learning Projects: Interprofessional student teams working together on projects that target community health needs.

Shared Clinical Placements: Interprofessional students working together in clinical education environments, possibly on DEUs or in PC clinics, and learning to observe team-based care.

Institutional commitment, training, and collaboration across departments are important factors contributing to the success of IPE, in addition to curriculum mapping and adequate resources (space, technology). Guided curriculum development and evaluation are founded upon frameworks such as the IPEC core competencies (Values/Ethics, Roles/Responsibilities, interprofessional communication, Teams, and Teamwork).

2.5 Increased Attention to Mental Health and Well-being

Stress, burnout, moral distress, and compassion fatigue are significant challenges for the nursing profession, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues. Awareness of the effect that nurse well-being has on themselves and patient outcomes is leading to increased attention to mental health, self-care, resilience, and wellness in nursing education.

This is done by proactively engaging students in learning about the threat of burnout and the signs and symptoms of conditions like anxiety and depression, but also in teaching ways to cope with the rigors of the field in the face of adversity and encouraging self-care (mindfulness, exercise, adequate rest) and resilience.

When nurses encounter adverse situations in the workplace, resilience training builds the tools to approach each situation without being overwhelmed by the stressors inherent to the work we do. Some curricula will have some discrete modules and other curricula will integrate wellness concepts across the entire program, which encompasses a holistic view of health, integrating mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of well-being.

There is also an emphasis on preparing nurses to meet the increasing mental health needs of the population. This will include developing clinical judgment, particularly in the area of psychiatric care, learning psychopharmacology, and developing interpersonal and communication skills for effective therapeutic interaction.

The specific challenges that accompany mental health nursing practice, such as traversing intricate legal and ethical domains (for example, pertaining to the Mental Health Act), and supporting patients, are also under scrutiny. This dual focus — not only promoting nurses’ own well-being but also supporting their ability to deliver mental health care — is central to a sustainable workforce and better patient outcomes.

Curriculum content has evolved to reflect a more holistic understanding of health and the role of nursing. It shifts away from being a purely clinical, disease-focused model to include population health; the effect of social determinants; the potential held by data and technology; an emphasis on collaboration; and the wellness of both the patients and providers. Overall, it is critical to preparing nurses to address the diverse and complex health challenges of the 21st century.

Part 3: Evolution of Teaching and Learning Approaches

In addition to what nursing students learn, how they learn is undergoing significant change, too. With current evidence and recommendations for active and learner-centred approaches to nursing education that promote understanding, critical thinking, and practice readiness, formal lectures are falling out of favour with nursing educators. Key pedagogical shifts are the adoption of competency-based education (CBE), the growth of online and hybrid learning models and the increase in active learning strategies.

3.1 Competency-Based Education (CBE)

The move towards CBE is a significant paradigm shift that the AACN strongly promotes through its 2021 Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. CBE emphasizes demonstrating specific, measurable competencies—what a student knows and can do—rather than the time spent in courses or covered content (“seat time”). The AACN Essentials define 10 domains and related competencies that graduates are anticipated to practice, guiding this transformation.

Competency-based education (CBE) aims to prepare more practice-ready nurses by ensuring they demonstrate the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to succeed in modern practice. In this way, learning expectations are made clear to students; it puts the student at the centre of the learning process; it promotes equity by emphasizing mastery over content knowledge for diverse learners, and it forces students to take ownership of their educational experience. The role of the faculty changes from lecturer to coach or facilitator, helping students achieve competencies.

But implementation is where the rubber meets the road. Faculty may be reluctant to abandon traditional teaching methods; students may need assistance adjusting to a more self-directed paradigm, and creating valid and reliable competency assessments is challenging. Assessment in CBE cannot be about an exam; it has to be multiple modalities (e.g., simulation, performance tasks, clinical evaluation) with multiple assessors across time, and it commonly occurs with rubrics that align with specific competencies.

Administrative barriers (e.g., curriculum mapping, documentation for accreditation [CCNE, ACEN], and adherence to state board regulations) are also present. Implementation will generally happen in phases over multiple years, beginning with faculty training, determining which curriculum mappings are necessary, piloting CBE in select courses, and tracking competency attainment over time through technology.

3.2 Online and Hybrid Learning Models

Online and hybrid (blended) learning existed before the pandemic but became significantly more widespread due to COVID-19 restrictions and are becoming a dominant trend. These models provide flexibility and accessibility, especially for students juggling education with work or family commitments. Online platforms have also converted didactic content into a format accessible via lecture recordings, interactive modules, discussion boards, and digital assessments. Hybrid models combine online components with in-person elements like skills labs or clinical simulations.

Models must be designed carefully to ensure engagement, interactivity, and high efficacy. With the aid of technology, content can be delivered, and virtual simulations and telehealth training can also be conducted. Although largely positive in its implications, the need for equitable access to technology and reliable connectivity to the Internet remains a potential drawback. On top of this, educators are challenged with balancing the ease of online learning with the necessity of hands-on development of skills and interactions with others — something many pre-licensure programs have to fill with a hybrid approach.

3.3 Interactive Learning Strategies

Alongside CBE and flexible delivery models, we have seen a broader shift towards active learning methods, which involve students as passive recipients of information and engaged participants whose critical and independent thinking processes are developed and deepened. This differs from passive approaches such as standard lectures. There are several active learning strategies commonly used in nursing education:

Simulation: As mentioned earlier, HFS, VR/AR and standardized patient scenarios offer immersive, hands-on experiences in which students engage in active knowledge and skill application. A debriefing post-use is essential to simulation as an active learning methodology.

Team-based learning (TBL) is an effective approach that involves individual preparation, readiness insurance tests, and team application tasks to discuss or resolve complicated issues. They have successfully used TBL to integrate genomics or similar topics.

Case studies and problem-based learning (PBL): students navigate real clinical cases, analyzing information, determining problems and proposing solutions, often in small groups.

Flipped Classroom: Students access foundational content (e.g., lectures, readings) online ahead of class so that in-person time is utilized for applying and discussing knowledge and engaging in problem-solving activities facilitated by faculty.

Andragogical Methods: Engaging Teaching Policies — Audience responders (polling), think-pair-share, etc.

These strategies work in concert with CBE because they allow students to practice and demonstrate competencies. They demand that faculty become facilitators, helping students inquire and apply knowledge instead of just transmitting information.

The movement toward CBE, flexible learning models, and active strategies is a paradigm shift in nursing pedagogy. Instead of memorizing nurtured knowledge, it is shifting toward actively applying, critically judging, and proving skills to better prepare graduates to meet the everyday challenges they will face as nurses in the 21st century. This is putting in the massive work of faculty development, curriculum redesign, and assessment innovation.

Section 4 — Challenge: Workforce and Educational Solutions

The larger health workforce ecosystem highly integrates nursing education into its operations. Many things affect how well schools can train enough qualified nurses to meet the population’s needs, such as a lack of teachers, difficulties in finding enough varied and suitable clinical placements, and the ongoing need to prepare graduates for quickly changing job roles. It is critical to respond to these challenges for the future of nursing education and the health system it serves.

4.1 Faculty Shortages

A long-standing and escalating shortage of qualified nursing faculty is the chief bottleneck to increasing nursing program capacity. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) found a national nurse faculty vacancy rate of 7.9% in 2023, which equates to nearly 1,700 open full-time positions. This shortage prevents nursing schools from being able to accept thousands of highly qualified applicants each year (65,766 in 2023) because the agency cannot provide the much-needed faculty, clinical sites, and other resources.

Several reasons lie behind the faculty shortage:

Ageing Faculty and Retirements: A large proportion of higher education faculty is near retirement age — it is estimated that one-third will retire by 2025.

Financial Compensation: Faculty pay is typically much less than nurses can earn clinically, particularly nurses with advanced degrees, so academia is often not as financially attractive.

But if you keep flying high, you will eventually run out of gas and die, thus leading to a statement like Educational Requirements: Most faculty positions may require or prefer a doctoral degree (PhD or DNP), but PhD enrollment is decreasing.

Scope and Demands: Faculty positions combine teaching, scholarship, service, and often clinical practice, and they can result in potentially heavy workloads.

Strategies to combat the shortage are many-layered and often involve academia and practice working together:

Financial Incentives: Advocating for increased federal and state funding, faculty salaries, loan forgiveness programs, scholarships for doctoral students/postdoctoral scholars, and tax incentives for preceptors/clinical faculty. Legislation such as the Nurse Faculty Shortage Reduction Act would cover federal wage differentials.

Academic-Practice Partnerships: The hiring of clinical and academic staff together has generated significant interest. Practice partners can also bolster faculty development.

“Grow Your Own” Programs: These programs would focus on finding and supporting promising graduate students into faculty positions, perhaps with tuition support.

Faculty Development and Support: Strong mentoring and leadership development programs (e.g., AACN LEADS) and resources to prepare faculty for teaching roles and address burnout

Flexible Roles: Providing part-time or adjunct opportunities and considering non-nursing faculty to teach foundational sciences.

Recommendation 2: Streamlining Pathways Using centralized application services (e.g., NursingCAS) to identify and fill vacant seats in programs to prepare future faculty

Recruitment and retention are critical for expanding nursing education, ensuring quality-based education, and advancing health equity through faculty diversity, so addressing the faculty shortage is essential for hiring faculty at nursing schools.

4.2 Ensuring a Varied and Sufficient Number of Clinical Placements

Clinical education is crucial for developing practice readiness, but finding sufficient, high-quality clinical placements for an ever-growing number of students is a continuous problem. Difficulty in obtaining clinical placements stems from competition for sites, the limited availability of preceptors, and the increased prevalence of a complex environment for practice. Moreover, placements should span a range of experiences in different practice settings (acute care, community telehealth, etc.) and a range of patients. This combination is vital for preparing graduates for the diversity of nursing practice and essential to equitable health outcomes.

These challenges are giving rise to innovative models and partnerships:

Dedicated Education Units (DEUs) are partnerships in which clinical experiences are organized around specific hospital units. Staff nurses (trained by faculty to serve as clinical instructors) and faculty collaborate closely. DEUs develop a more structured and supportive learning environment, strengthen the link between academia and practice, and simultaneously increase student preparedness and recruitment/retention potential.

Academia-Practice Partnerships (APPs): APPs can occur over broad regions with multiple schools and healthcare systems partnering to facilitate placements, share faculty, coordinate research, and align curricula. Successful APP initiatives are predicated on mutual trust, alignment of goals, support from leadership, and clear communication. Such partnerships include those allowing students to work as nurse technicians during COVID-19 surges or leveraging electronic health records for telehealth training.

Simulation Validation: While this reality is not a substitute for real-world experience, high-fidelity simulation and skills can replace very few specific hours in most clinical placements. However, this varies considerably based on the limits set by governing boards.

Community-Based Placements: Pursuing placements outside the hospital in public health departments, schools, clinics, and home health agencies exposes physicians-in-training to population health and SDOH.

Strategies such as these depend on substantial collaboration and resource sharing between educational institutions and clinical partners to offer students the varied, high-quality experiences that contemporary practice requires.

4.3 Preparing Nurses for Evolving Roles in Healthcare

As the healthcare environment evolves, it necessitates nurses who are clinically competent, flexible, critical thinkers, leaders, and lifelong learners. The healthcare ecosystem is evolving to require new skill sets, and the nursing workforce is being thrust into new roles beyond a hospital setting. This involves:

Encouraging Lifelong Learning and CPD: Early in a nurse’s career, promoting the expectation that learning will continue throughout their practice is essential. Educational programs train you to ask questions, think critically, and become agile. CPD consists of pedagogically oriented continuing activities such as workshops, certifications, advanced degrees, online learning, and reflective practice to remain competent and up-to-date with technology, evidence-based practice, and care delivery models.

Nurse Leadership Skills: Nurses are taking on more leadership positions and responsibilities, and they need to manage the change and teams and advocate for patient and policy contributions to the systems. Curricula include leadership development, quality improvement principles, and systems thinking.

Fostering Critical Thinking and Clinical Judgement: As patient complexities and technology advance, the skills to evaluate a situation, make appropriate decisions, and adjust care are essential. Pedagogies like simulation, case studies, and CBE explicitly aim to develop these higher-order thinking skills. This need is further emphasized by the new Next Generation NCLEX (NGN) exam, which focuses on clinical judgment.

These challenges are interwoven: overcoming the faculty shortage is critical to increasing enrollment and educating more nurses; new clinical placement models are necessary to ensure vital clinical education at the bedside and the curriculum to prepare graduates to succeed in the rapidly changing roles ahead. One way to help connect education and practice is through academic–practice partnerships, which can tackle issues like helping to recruit faculty, creating new clinical placements, and ensuring education meets the needs of practice.

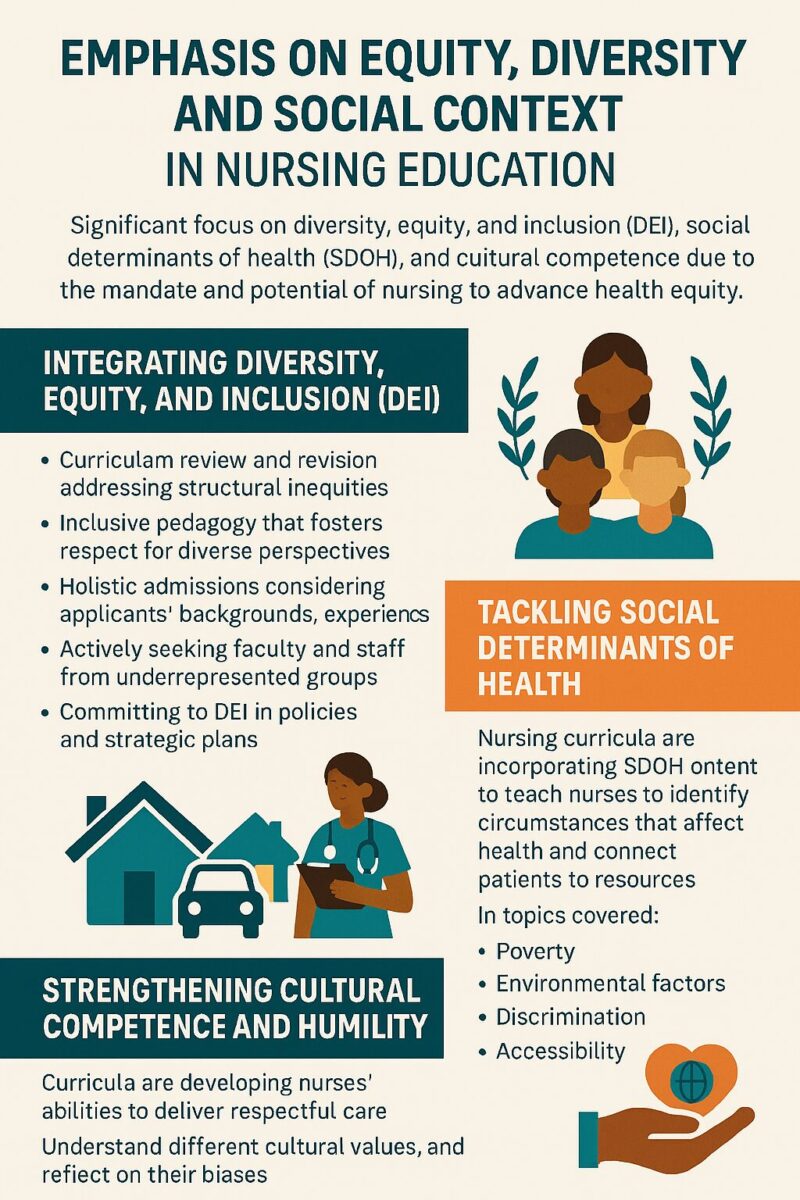

Section 5: Emphasis on Equity, Diversity, and Social Context.

A defining trend in nursing education is the significantly increased emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), social determinants of health (SDOH), and cultural competency. This focus stems from recognising persistent health inequities and the nursing profession’s ethical mandate and unique potential to advance health equity for all populations.

5.1 Integrating Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

There is a gradual shift among nursing education programs from treating DEI as isolated issues to incorporating these principles across the curricula and institutional climate. The AACN Essentials specifically embraced DEI as an interprofessional core concept across all 10 domains. This integration requires intentionality , blurring systemic details.

Methods for integration include:

Curriculum Review and Revision: Examining existing curricula to identify biases, ensuring content reflects diverse populations, and addressing health disparities, structural racism, and systemic inequities per the guidelines.

Inclusive Pedagogy involves using teaching methods that foster inclusivity and respect for diverse perspectives, ensuring that all students feel included and welcome in the classroom. This includes training faculty in implicit bias and microaggressions.

Holistic Admissions: This is a multifaceted approach that does not rely solely on quantitative metrics (GPA, test scores) and takes into consideration a myriad of factors such as applicants’ backgrounds, experiences, leadership potential, and ability to overcome obstacles in an effort to create a student body that is more representative of the population served.

Faculty and Staff Diversity: We are actively seeking faculty and staff from underrepresented minority backgrounds to be role models and bring varied perspectives.

Institutional commitment: Integration of DEI at the mission, vision, or values statement level in its strategic plans, policies, or other documents with explicit accountability structures.

Realising health equity demands that nursing education integrate equity as a foundational lens applied to the totality of the curriculum, pedagogy and institutional practice. Staying on this course means being introspective about how common content and practices may uphold inequities and intentionally working to eliminate those boundaries.

5.2 Tackling SDH (social determinants of health)

Recognising and addressing social determinants of health (SDOH)—the circumstances that influence health status—has become a necessary component of nursing practice and a critical means for advancing health equity. Nursing curricula incorporate SDOH content to prepare nurses to identify the impacts of SDOH on health, screen patients for social needs (e.g., food insecurity, housing instability), and connect patients to community resources.

This integration happens partly through didactic content that incorporates issues such as poverty, racism, discrimination, education level, environmental factors (air/water quality), accessibility to care and experiential learning. These will then be applied in community settings, working alongside community organisations and experiencing simulation scenarios representative of vulnerable communities and societal issues. Frameworks for this curricular evolution include the NLN’s Vision for Integration of SDOH and the AACN Essentials (including Domain 3: Population Health and the concept of SDOH).

5.3 Strengthening Cultural Competence and Humility

Nurses are called to grow their cultural competence and humility as we care for a more diverse population. It is to be aware of different cultural values and beliefs around health, to understand personal biases, to know how to communicate effectively across cultures, and to give care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences and needs. Curricula include content on cultural sensitivity, culturally competent care models, trauma-informed care, and strategies for working with interpreters. Part of this process is learning experiences from interacting with patient populations of different backgrounds in clinical settings and simulations, among other activities. It aspires to develop nurses who can deliver equitable, person-centred care to all individuals, irrespective of their background.

Additionally, educating nurses to promote health equity requires direct instruction in policy analysis and advocacy skills. Health inequities are frequently rooted in systemic issues and policies. To address them, nurses must understand how policies create or reinforce inequities and how and where to advocate for change across the levels. This broadens the nurse’s role beyond individual care, including civic engagement and system transformation as essential professional duties.

6. Specialization and Pathways to Advanced Education

Complexity of healthcare, workforce demands, and technological advancements were the reasons that led to the most obvious trend: specialization and advanced education. Nursing education programs are responding by creating more explicit paths for education progression and creating specialty tracks to address the increase in need for nurses with expertise in various forms of practice.

High-Demand Specialties and Certifications in 2025

Here are a few nursing specialties that will see high demand and growth through 2025, most of which require advanced education (Master’s or Doctoral degrees) and certification:

Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs): This category, comprised of Nurse Practitioners (NPs), Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs), Certified Nurse Midwives (CNMs), and Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNSs), has strong growth projections (38% overall from 2022-2032).

The role of Nurse Practitioner (NP): The shortcomings in availability of physicians in primary care continue to create a demand for trained nurse practitioners (NPs), which are fast becoming the go-to providers for chronic diseases related to an ageing population, as well as to fill the gap of care in badly underserved areas. Several states are increasing NP’s scope of practice, resulting in more autonomy. The most common NP specialties in high demand are Family NP (FNP), adult-gerontology NP (AGNP), psychiatric mental health NP (PMHNP), and acute care NP. The median salaries are significant, often more than $125,000.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) : CRNAs are one of the highest-paid nursing professionals, given their high level of autonomy in administering anesthesia. Demand is vigorous (estimates vary from 9-38% growth, depending on who you ask and when you ask them), propelled by surgical necessity. A doctoral degree is increasingly the default entry requirement. Average salaries frequently reach or top $200,000.

Certified Nurse Midwives (CNMs): CNMs specialize in women’s health overall, particularly prenatal, delivery and postpartum care, and the demand for these professionals is also increasing, thanks to growing popularity behind holistic approaches to having the baby. Salaries often exceed a median of more than $115,000.

Clinical Nurse Specialists(CNSs): CNSs are specialized RNs that work within a specific patient population or within a specialty area to help improve patient outcomes and educate nursing staff.

Less-Changing, Nursing Informatics: As the healthcare sector increasingly grows to be data-powered and technology-reliant, informatics experts play a very important role in managing health information systems, analyzing data for care enhancements and linking the space between clinical practice and IT. The program presents compelling career outcomes, and related positions like medical/health services managers are expected to grow 28% in the coming years. Salaries generally start at $80,000 and can exceed $130,000.

3: Geriatric Nursing: As the population ages (estimate 77 million us residents over the age of 65 by the mid-2030s) a huge demand is expected for nurses who specialize in caring for the elderly, managing chronic disease, and promoting healthy aging. This includes positions for Geriatric skilled RNs as well as advanced practice Geriatric NPs.

Increase in Mental Health Issues: The growing awareness and prevalence of mental health issues have also been fueling the demand for more psychiatric mental health NPs (PMHNPs) and RNs with specialized skills in mental health. What Marital Health for NP High Performance Practitioners Do: PMHNPs provide psychotherapy, medication management, and nursing planning.

Nurse Educators: Needs for nurse educators (those who fulfill the faculty shortage) come only from graduate-level prepared (Master’s or Doctorate) nurse educators who teach in academic settings or clinical settings.

Telehealth Nursing: As virtual care goes mainstream, demand rises for nurses who can provide telehealth delivery, remote monitoring and digital communication.

Other growth areas include palliative/hospice nursing, oncology navigation and pediatric critical care. In-depth variable are those specialties for which certifications are commonly available and can show expertise.

6.2 Trends in Attainment of BSN and Higher Degree

BSN (Bachelor of Science in Nursing, made the minimum for entry-level practice, with progression to move towards graduate degrees (MSN, DNP, PhD).

BSN as Entry-Level: Leading nursing organizations and reports such as Future of Nursing have long promoted a greater percentage of BSN-prepared nurses, pointing to associations with improved patient outcomes as well as critical thinking and leadership skills. Although we did not reach our goal to have 80% of the nurse workforce be BSN-prepared or higher by the year 2020, the profession is responding significantly.

Today, more than 70 percent of the RN workforce holds a BSN or higher degree, according to recent data. The BSN was the most common entry-level degree for those new RNs in 2022 for the first time (45.4 percent). Hiring: Employers highly prefer or demand hiring BSN-prepared nurses. There are dozens of RN-to-BSN programs designed to help associate degree or diploma nurses further their education.

Expanding Graduate Education: High demand for MSN and DNP/PhD-level nurses to fulfill the roles of APRNs, nurse educators, researchers, administrators, informatics specialists Although on the heels of substantial growth, there are recent declines in MSN and PhD enrollment, the proportion of the workforce with graduate education has nonetheless swelled. Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) programs, emphasizing practice leadership, have increased significantly. It is the demand for APRNs that is a chief driver of graduate enrollment.

This general trend illustrates the increasing complexity in health care, which requires a more educated nursing workforce with capabilities in advanced clinical practice, leadership, improvement in quality of care, translation of research into practice, and competency in systems thinking. As a response, educational institutions are scaling graduate programs and designing seamless education pipelines (for example, RN-to-MSN and BSN-to-DNP).

Table 2: Selected High-Demand Nursing Specialties for 2025

| Specialty Area | Degree/Role Examples | Key Drivers | Projected Growth (Representative) | Median/Average Salary (Representative) | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Practice (APRN) | NP, CRNA, CNM, CNS | Physician shortages, aging population, expanded scope of practice, chronic disease | 38% (APRNs 2022-32) | $125k+ (NP), $195k+ (CRNA) | |

| Nurse Informatics | Informatics Specialist | Technology integration, EHRs, data analytics, need for efficiency | 28% (Related Health Mgrs 2022-32) | ~$80k – $134k | |

| Geriatric Nursing | Geriatric NP, RN | Rapidly aging population, increased chronic illness prevalence | High demand (driven by demographics) | ~$76k (RN w/ skills), $80k+ (GNP) | |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health Nursing | PMHNP, RN | Increased mental health awareness/needs, provider shortages | High demand | ~$155k (PMHNP) | |

| Nurse Educator | Faculty, Clinical Ed | Nursing shortage, faculty shortage, need for qualified instructors | High demand (driven by workforce needs) | ~$105k | |

| Telehealth Nursing | Telehealth RN/NP | Increased access needs, convenience, technology adoption | High demand | ~$95k |

Note: Salary and growth figures vary by source, location, experience, and specific role. Data presented are representative examples found in the source material.)

Conclusion

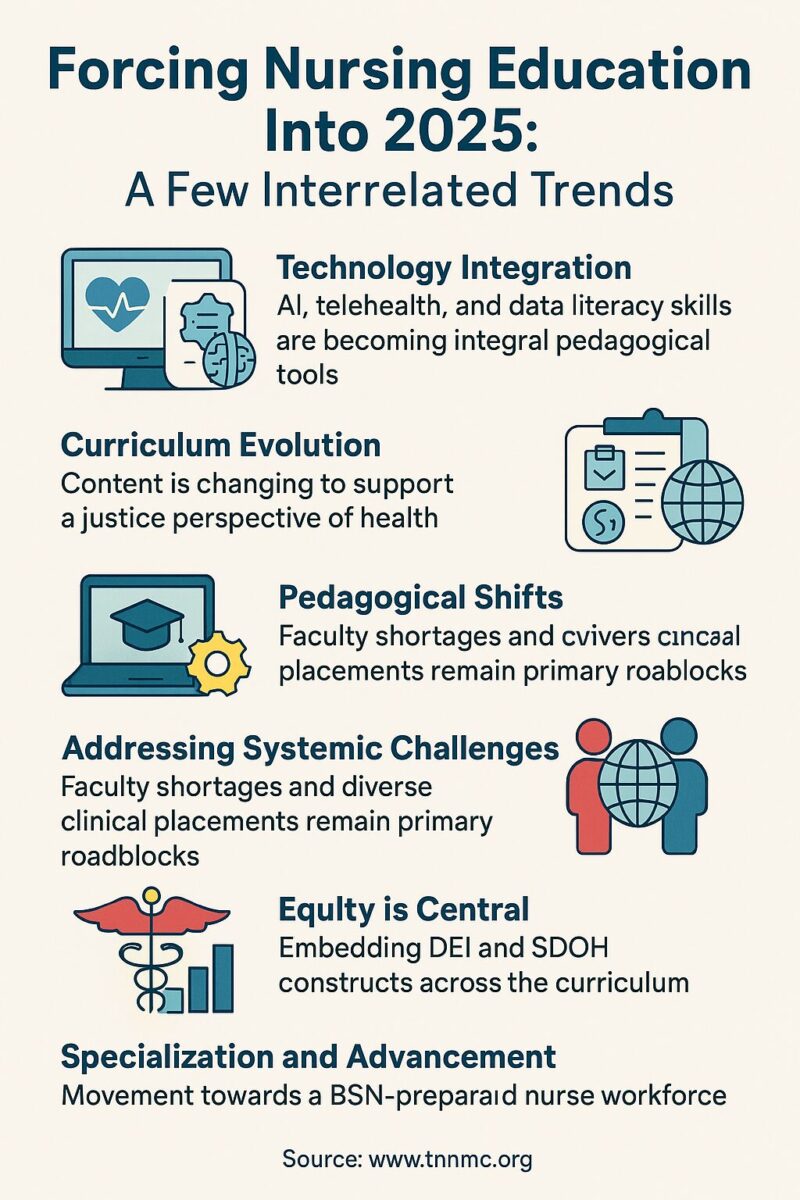

Forcing Nursing Education Into 2025: The transition to an ever-evolving workforce for an ambiguous industry! A few interrelated trends are apparent:

Technology integration is transitioning from simulation (HFS, VR/AR), AI, and telehealth, which were once ubiquitous peripheral teaching and learning tools, to integral pedagogical tools. This entails a substantial investment in infrastructure and faculty training, as well as an emphasis on nurturing students’ digital data literacy, data interpretation and ethical reasoning skills to effectively integrate these as augmentation of rather than replacements to core nursing competencies.

Curriculum Evolution: Content is Changing to Support a Justice Perspective of Health This enables graduates to address SDOH, leverage data, understand the relevance of genomics, collaborate within teams, and maintain self-resilience.

Pedagogical Shifts: The transition toward competency-based education (CBE), mapped to frameworks such as the AACN Essentials, marks a paradigm shift toward outcome-focused learning and practice readiness. This is reflected in the increased use of flexible online/hybrid models and active learning strategies that have fostered critical thinking and skill application.

Addressing Systemic Challenges: Ongoing shortages of faculty members and issues related to finding diverse clinical placements are still primary roadblocks. New, innovative strategies and powerful academic-practice partnerships are critical to increasing capacity, improving faculty recruitment/retention and providing appropriate clinical experiences.

Equity is Central: Pursuing health equity drives much of the educational change. This entails embedding DEI and SDOH constructs across the curriculum, employing inclusive pedagogies and admissions processes, and readying nurses to engage in policy advocacy.

Specialization and Advancement: The movement towards a BSN-prepared nurse workforce as standard practice, along with the increasing demand for advanced preparation and specialists (informatics, geriatrics, mental health), reflects an increased need for defined educational ladders and strong graduate programs.

It takes a concerted effort from educational institutions, clinical partners, policymakers, and accredited bodies to navigate these trends. Directing resources toward faculty development, technological infrastructure, curriculum redesign, and strong academic-practice partnerships will be critical. Embracing these innovations will enable nursing education to effectively cultivate a diverse, competent, and resilient nursing workforce to lead and flourish in the healthcare landscape of 2025 and beyond, thus ultimately facilitating improved health outcomes and increased health equity for all.